For more than a decade, my colleagues and I at the Department of Landscape Architecture have been teaching and researching landscape heritage through immersive, project-based fieldwork with our students. Together, we’ve walked through historic towns, traced cultural motifs, interviewed the locals, and built exhibitions that attempt to honour the stories embedded in cultural landscapes.

This post is adapted from my publication on heritage documentation, and it reflects on our decade-long journey of teaching, observing, and experimenting with different ways of recording landscape heritage. More importantly, it highlights how our methods have shifted from mostly traditional tools to increasingly digital forms of documentation and exhibition. Drawing from seven heritage projects conducted in Malaysia and Indonesia, the insights show that analogue and digital methods don’t compete with each other; rather, they complete each other.

Why Documenting Landscape Heritage Still Matters

Heritage is more than architecture; it lives in landscapes, in rituals, routes, water systems, vegetation, craftsmanship, and shared memories. Documenting these layers is essential for preservation and planning, intercultural understanding, strengthening community identity, and educating future practitioners and the public.

Students often begin these projects with curiosity, but they end with a deeper appreciation of how culture, ecology, and history intersect in everyday places. This personal connection is one of the most powerful outcomes of heritage-based learning.

The Tools We Used

Across the seven projects, from Bali and Bandung to Kota Bharu, George Town, and Taiping, we used an evolving toolkit of analogue and digital methods.

1. Traditional, Hands-on Documentation

These methods activated the senses and grounded students in the physicality of heritage:

- Hand-drawn measured drawings

- On-site sketches

- Mapping using pen and paper

- Charcoal tracings

- Clay and plaster mouldings of motifs

- Interviews and oral histories

- Observation checklists

- Photography and manual note-taking

Students often worked outdoors for hours, sometimes in rain, cramped spaces, or busy streets, but these hands-on methods trained them to see more attentively.

2. Digital Documentation

As technology became more accessible, our methods expanded:

- Drone photography/videography

- Digital photography/videography

- Interactive maps

- Digital drawings and renderings

- Websites, e-books, infographics

- Virtual Reality (VR) & Augmented Reality (AR) features (later projects)

The Taiping project, for instance, integrated drones, Webflow-based heritage portals, holographic displays, and immersive digital storytelling, making it one of our most comprehensive digital exhibitions.

How We Teach Landscape Heritage: A Three-Part Journey

Each project followed a structured yet adaptable process.

1. Before the Visit: Building Context

- Students conducted desktop studies

- Identified heritage attributes

- Used maps and literature

- Listened to lectures from lecturers and invited experts. For Taiping, they organised public webinars.

This phase lays the foundation: students learn to ask better questions before stepping on-site.

2. During the Visit: Immersion, Discovery, Reflection

On-site work is the heart of the experience. Students:

- Collected data in teams

- Observed how people use spaces

- Interviewed custodians and residents

- Photographed and sketched heritage elements

- Created mouldings and tracings

- Conducted daily critique/reflection sessions

These nightly discussions sharpened their analytical thinking and helped them refine their next-day strategies.

3. After the Visit: Turning Data Into Narratives

Students synthesised their findings through:

- Books and posters

- 3D models and technical drawings

- Video documentaries

- Digital exhibitions, websites and oonfographics

Earlier cohorts used PowerPoint, CAD, and manual models. Post-pandemic cohorts adopted Canva, Miro, shared drives, and collaborative cloud platforms, transforming group workflows dramatically.

Exhibiting Heritage: From One-week Shows to Global Portals

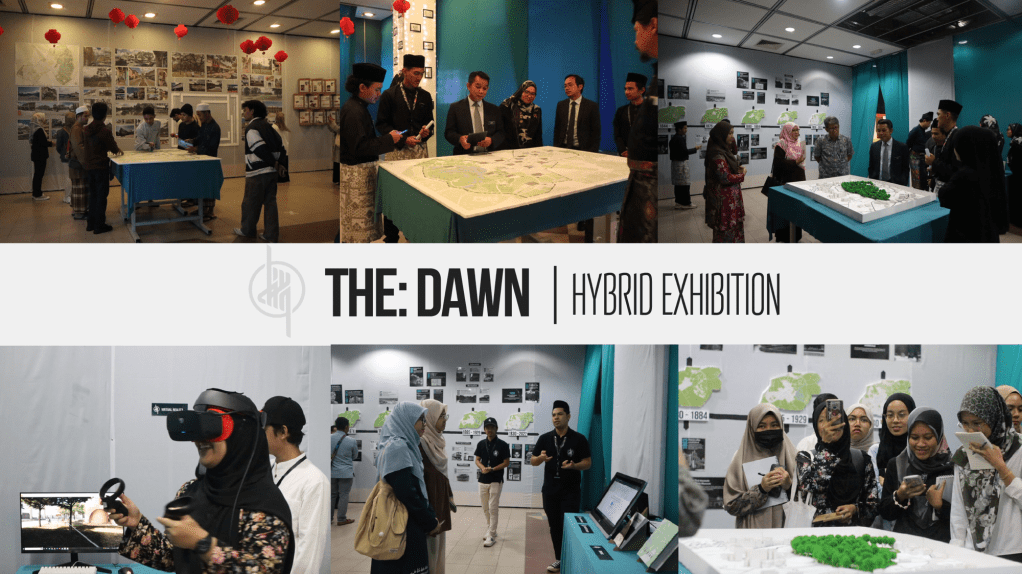

Exhibitions have always been the climax of each project. Traditionally, they consisted of physical models, posters, sketch collections, plaster mouldings and printed books.

These physical displays created tactile, memorable experiences, but they were hard to store and limited to a one-week showcase.

The Shift to Digital Exhibitions

The Georgetown project (2019) marked the turning point with a full website archiving all project outputs. From there, digital exhibitions became a new norm. By 2022, the Taiping project featured an interactive website, virtual and augmented reality elements, animated maps, holographic visualisation, and e-books. This expanded access from “one week in a hall” to “anyone, anywhere, anytime.”

So What Did We Learn?

After reviewing a decade of teaching, documentation, and exhibition, several insights became clear:

1. Traditional methods make students attentive and grounded. Sketching, moulding, and on-site observation sharpen skills that no digital tool can replace.

2. Digital methods amplify reach and richness. Drones, websites, and VR add layers of insight and accessibility unimaginable in earlier years.

3. The hybrid approach is the future of heritage documentation. Combining both methods results in more comprehensive datasets, more creative exhibitions and more inclusive audience engagement.

4. Reflection is as important as documentation. Each project helped refine the next, a continuous process of evaluating tools, workflows, and teaching strategies.

5. Heritage work is inherently interdisciplinary. It blends culture, ecology, design, community engagement, storytelling, and technology.

Looking Ahead

The future of landscape heritage documentation is exciting. With emerging tools such as LiDAR, GIS-based storytelling, machine learning for pattern detection, and immersive exhibitions, we have more ways than ever to understand and preserve our landscapes.

Yet the heart of this work remains the same:

To honour the stories held in our environments, and to pass them meaningfully to the next generation.

This reflection from our seven projects reinforces that documenting heritage isn’t just about tools or outputs. It’s about cultivating curiosity, empathy, and responsibility toward the landscapes we inherit and shape.

Read the full paper here: “Transitioning from Traditional to Digital Methods: Insights on Documenting and Exhibiting Landscape Heritage”